I took the train to Sambalpur the day after I flew to Bhubaneswar, Odisha, a state on India’s central east coast. Ranjan Panda met me at the station in his little blue car and took me to a modest hotel that would save me money during my stay. I had dinner at its restaurant — probably where I made the mistake that soon led to stomach problems. I enthusiastically ate the raita, which has raw cucumber and sometimes other vegetables in it. It’s a tangy, cooling, yogurt accompaniment to spicy curries. Having had Surendra’s organic greens in Khajuraho and then fairly safe food in Delhi, I was not vigilant enough.

The next day I joined Ranjan on a field trip for students from the local college. He wants young people to know more about the region where they live, and he works with a group called Patang, which does many outreach programs for young people in the city as well as with rural people. We visited fishermen on the Mahanadi River and heard about their attempts to protect a particular species of fish they value, the mahseer, whose numbers are severely depleted because of a dam, pollution, and overfishing. The traditional fishermen also have to contend with a “fish mafia,” whose members use explosives to kill more fish (sounds crazy but I’ve heard this before in another part of India) to make more money—thus harming the species and robbing the responsible fisherfolk of their livelihood.

Ranjan talked to the students in their local language, though most of them knew English and some spoke it well. There are many local languages in Indian states, and local variations within the states. There is Oriya, the language of Orissa or Odisha. And there’s also Sambalpuri—which Ranjan said is closer to the Hindi spoken in the center of the country than it is to Oriya. I couldn’t understand what he was telling them, but they listened attentively and he made them laugh from time to time, a good teacher.

We stopped at a fishing village where the students talked to fishermen and saw them demonstrate the way they throw their nets. Feeling woozy in the strong sun, I had to retreat to the shade up the hill from the riverside long before the demonstration was over. It’s pretty warm here, but not fully hot. Meaning not over 100 yet! It’s actually not been as bad as I feared, there having been some clouds and haze to hold the temperature down.

It was Sunday and seemed to be a day off for the villagers. Men and women were in the shallow water near the riverside bathing, the women washing clothes, children playing in the water.

The young “sarpanch” – the village leader – had arranged lunch for all of us, which we ate under spreading mango trees on the grounds of some official building a short drive down the road. The temperature dropped dramatically in the shade of all those trees, proving what I hear again and again about the value of trees to protect soil, animals, and people from the strong sun here, and to promote rain and groundwater. The loss of trees in a once widely forested India began in colonial days and is still ongoing, but pockets are protected in some places in the form of community forests. Ranjan told me about his work with some of the tribal people who still live in the forest and manage it well.

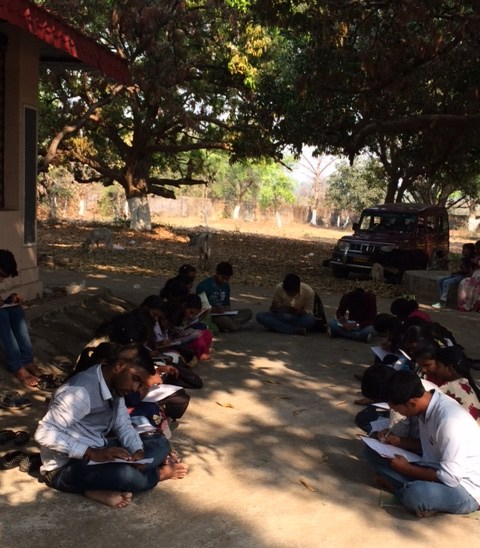

After lunch the students wrote their impressions of the day’s field trip, what they had learned and what reflections it prompted. Ranjan was born, raised and educated here—and has been working for years now to publicize wrongs and help people, so the local farmers and fishermen know him as do local business people. He’s clearly well-respected. The students applauded at the end of the program that day and said how proud they were of him.

I met Ranjan’s wife and daughter over tea at his house on the way back. The daughter is 14, tall, pretty, sassy and bored with her provincial town. Her name is Prakriti, which means nature, but her nickname is Kusi, which means happy. She thinks she wants to go to the US, having watched a lot of TV. His wife, Aparajita or Ajita, teaches political science at a local university and is a lovely woman who keeps everything running smoothly and cooks from scratch all three meals each day. She says she loves to cook and likes to be organized. Sleeping in on Sunday means till 7, when she can have tea and read and not get up to cook so early. They also have a 21-year old son who was away at school. I got invited to several meals—breakfast and lunch, as they don’t eat dinner until 10 or even later and they knew that wouldn’t work for me.

The first special breakfast was scheduled for the following morning, when I awoke feeling not so great—exhausted and achy and with diarrhea. But as I wasn’t nauseated and Ajita was making South Indian specialties because I had said how much I liked them, I went for breakfast and ate—just not quite as much as I often do. Then I went back to bed until late afternoon. A few hours into the rest time I took an antibiotic, feeling fairly sure I had a bacterial infection (the raita from Saturday night a likely culprit).

The rest helped some, and as the day cooled we went outside Sambalpur to the university where Ranjan had studied sociology. There we picked up the retired professor who had gotten Ranjan interested in natural resources, water, farmers, fishermen, and tribal customs—and essentially changed the course of his life. He’s been a researcher, writer and activist on these issues ever since. We went together to see the long earthen dam on the Mahanadi River, modeled on our TVA, which is now the source of interstate disputes as well as the cause of multiple damages to the river system.

Back to bed. The next morning the plan was to go with Ranjan at 8 to buy fresh fish, as Ajita had learned I liked fish and was going to make some special dishes for that day’s lunch—a large meal eaten around 2. The local fishermen bring their catch in early in the morning to a spot on the edge of town and apparently they sell out fast. Ranjan selected one—not the mahseer, some other local species—and the fisherman scaled it and then cut it up expertly with some scary sharp instruments.

After the foray to the fish market, I said I thought I had better rest again to save energy for the rest of the day. I ate eggs and toast at the hotel and slept three more hours. That, along with the second dose of antibiotic twelve hours before, seemed to turn the corner.

We had the special fish lunch, which Ajita had somehow prepared before and after going to campus: not just fish (in two different dishes), but dal, and various vegetables.

After lunch we drove to a town about an hour away called Jharsuguda, in the heart of Odisha’s—and India’s—coal and steel industry. There I saw a nightmare that I’ll write about in next post.

What was the nightmare you saw? Is there a missing paragraph?

LikeLike

“There I saw a nightmare that I’ll write about in next post.” Did you see this sentence or something else? I had a lot of trouble getting Sambalpur posting right. Maybe it was the wifi here, but I would make changes and additions over and over again and they wouldn’t be captured. Finally I thought I had it right!

LikeLike